India is gradually unlocking its economy after a shutdown that lasted more than two months. But it’s unlikely to be business as usual for millions of retailers, small enterprises and factories, writes the BBC’s Nikhil Inamdar.

By all accounts, reversing the disruption caused by India’s lockdown will be a long haul – and the price businesses, especially small firms, have paid is just starting to become clear.

“At least 20% of neighbourhood mobile shops that sell smartphones may never reopen again,” says Arvinder Khurana, president of India’s mobile retailers association.

The reasons are many, he adds – on the one hand, owners have fled the cities and are yet to return, and on the other, with job losses mounting and banks averse to offering consumer loans, there is no demand for high-end phones.

According to India’s retail association, sales of non-essential items – such as clothes, electronics, furniture – fell by 80% in May. Even sales of essential goods – such as groceries and medicines – dipped by 40%.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

The near future looks uncertain as infections rise – India has recorded nearly 200,000 cases so far, with several record single-day spikes in the last week.

But the government is yet to announce uniform procedures for businesses that are reopening – so sales are expected to slide further down, even as high-street shops, malls and other commercial markets are scheduled to reopen next week.

Not all businesses were closed during the lockdown – those deemed essential, from agro products to power, food supply to healthcare – continued operating. And more businesses have been allowed to reopen since early May.

But they are all bogged down by low demand, falling exports, labour shortages and new rules of operation requiring social distancing and other safety measures to curb the pandemic.

In a recent interview, the CEO of one of the world’s leading motorcycle manufacturers, also said there isn’t enough clarity from the government.

“I am not seeing that smooth, concerted, rhythmic movement towards unlocking,” says Rajiv Bajaj, managing director of Bajaj Auto.

- Why is India reopening amid a spike in cases?

- India’s bailout may not be enough to save economy

- Covid-19 plunges Indians’ study abroad dreams into turmoil

- Trouble ahead for India’s fight against infections

Mr Bajaj, a vociferous critic of the lockdown, was speaking to India’s opposition leader, Rahul Gandhi. “An aligned approach is required… I am really distressed because it is a Herculean task to open up,” he told Mr Gandhi.

And the effect on production is evident in India’s manufacturing data, which contracted for the second month in a row.

“Production is down by 50% and demand is very weak,” says Kshitij Ghai, who owns a textile mill that produces acrylic fabric in the northern city of Ludhiana.

He says he is unable to bring operations back to optimal capacity.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

“I haven’t even received payments for goods sent back in January and February. It is very difficult to ask dealers for money, because they themselves haven’t had any sales.”

But expenses have shot up due to compliance costs such as disinfectants, sanitisers, thermometers and masks for workers.

The exodus of migrant workers from cities during the lockdown has also meant severe labour shortages for some businesses.

At a construction site in the capital Delhi, where one of the country’s largest real estate firms, Raheja Developers, is erecting a residential building, the labour strength has dropped by 40% since the pandemic hit India.

“This is still a better situation than other construction sites around Delhi and Gurgaon, as we are among the few companies that have labour on payroll as opposed to daily wages,” says executive director Nayan Raheja.

But he says this will cause delays, and extend the project’s timeline.

Bleak months ahead

None of this bodes well for a quick recovery, especially for an economy that was already reeling from a slowdown.

India’s economy grew at 4.2% in the 2019-20 financial year – its slowest pace in nearly a decade – according to data released by the government last week.

For the first three months of this year, which overlapped with the first week of the lockdown, the country’s GDP expanded by a measly 3.1% – partially the result of businesses closing.

But economists predict a further slide downward – India’s GDP for the 2020-21 financial year is likely to contract between -7% to 0%, the worst technical recession since the 1970s.

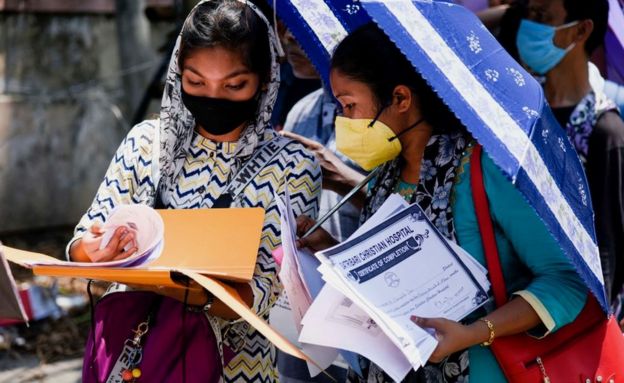

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

While the easing of restrictions will lead to a recovery, they expect it will take up to three months for economic activity to reach even half the level it was at before the outbreak.

Meanwhile, the rising number of Covid-19 cases has put Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government in a Catch 22-like situation.

“Increased economic activity will come at the inevitable cost of elevated risk of higher infection rate,” says Sonal Verma, an analyst at Nomura Global Research.

And most economists have been disappointed by the government’s economic response. India’s central bank has announced a raft of measures including rate cuts and moratoriums on loans. And the government has announced a $266bn (£212bn) stimulus, including a range of liquidity measures and reforms.

But, by most calculations, what they will end up actually spending amounts to a minuscule 0.8 to 1% of GDP. The consensus is that this isn’t sufficient to boost demand, spur growth or avert a spate of bankruptcies.

And it seems to be a widely-held opinion – ratings agency Moody’s downgraded India’s sovereign rating to the lowest investment grade for the first time in 22 years.

Courtesy: BBC