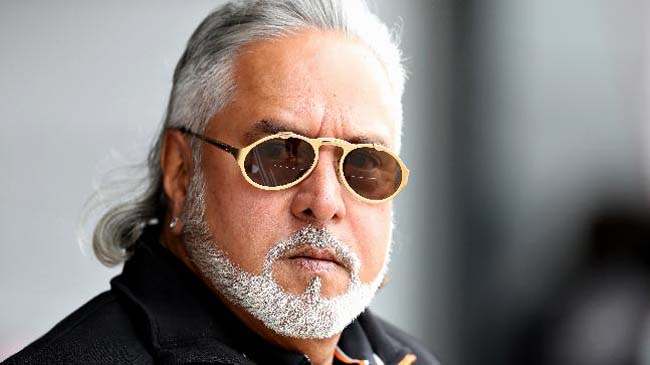

A court in the United Kingdom will decide on Vijay Mallya’s extradition to India on Monday to face charges of financial irregularities running into thousands of crores but the businessman is unlikely to return anytime soon.

Agencies

London, December 10:

A court in the United Kingdom will decide on Vijay Mallya’s extradition to India on Monday to face charges of financial irregularities running into thousands of crores but the businessman is unlikely to return anytime soon.

The 62-year-old former boss of Kingfisher Airlines has been on bail since his arrest on an extradition warrant in April last year. He has contested that the extradition case against him is “politically motivated” and the loans he has been accused of defrauding on were sought to keep his now-defunct airline afloat.

“I did not borrow a single rupee. The borrower was Kingfisher Airlines. Money was lost due to a genuine and sad business failure. Being held as guarantor is not fraud,” he said in a post on Twitter recently.

“I have offered to repay 100 per cent of the principal amount to them. Please take it,” the flamboyant businessman tweeted earlier.

A joint team of the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) and Enforcement Directorate (ED) led by CBI joint director A Sai Manohar left on Sunday for the United Kingdom for the court proceedings.

Monday’s judgement by the Westminster magistrates court in London may or may not be on the lines expected in New Delhi, but even if judge Emma Arbuthnot rules that there are no legal bars to his extradition and recommends it to the home secretary, Mallya (and India) will have opportunities to appeal in higher courts.

The Indian government would also have 14 days to file leave to appeal to the high court there, seeking permission to appeal against a decision not to extradite.

Besides, depending on the timing and how the Brexit imbroglio unfolds, he could also approach the European Court of Justice, which is known to be lenient on grounds of human rights. The final decision to extradite rests with the home secretary.

Since India and the United Kingdom signed an extradition treaty in 1993, several key individuals have been sought by India, such as Nadeem Saifi (Gulshan Kumar murder case), Ravi Sankaran (navy war room leak), Tiger Hanif (1993 Gujarat blasts), but none were followed so closely as the flamboyant Mallya’s case.

As Tiger Hanif’s case shows, even if an individual loses all legal challenges, extradition cannot happen until the home secretary signs it off. Having lost in courts, Hanif made a ‘final representation’ in 2013 to the home secretary, who is yet to take a decision on his extradition.

Mallya’s case essentially revolves around whether there is a prima facie case against him, and whether it amounts to a crime according to the laws of both countries as stipulated in the extradition treaty.

The amount outstanding against Mallya has been mentioned as over Rs 9,000 crore, but the case documents mention the alleged dishonest obtaining of loans “in the amounts of Rs 1,500 million, Rs 2,000 million and Rs 7,500 million during October and November 2009”.

While Mallya’s team insists there is no prima facie case and that the inability to return loans to his now defunct Kingfisher Airlines was due to a “genuine business failure”, India has alleged “three chapters of dishonesty” on his part.

The “three chapters”, according to lawyer Mark Summers representing India, are alleged misrepresentations made to banks to secure loans, what was done with the loans secured, and what Mallya and his companies did when banks recalled the loans.

Some of the words and phrases used by Summers in court were: “squirreling away” of funds, “playing round robin” by moving funds across banks, and “malafide intentions” on the part of Mallya and his companies.

Besides the ground of risk to human rights in Indian prisons, Mallya’s team has stated in the court that he has offered to settle with the banks, but also claimed that he is sought for political considerations in India, where he would also be subjected to “media trials”.

Four expert witnesses presented by Mallya’s team raised questions and doubts about the state of banking, prisons, politics and the judicial system in India. The conditions, they alleged, would not only pose a risk to his human rights but also amount to “extraneous considerations” and “abuse of process”.

India submitted thousands of pages of documents that needed to be carted in trolleys; Mallya’s team produced a similar number of documents.

Judge Arbuthnot, who called the case a “jigsaw puzzle”, said it was “blindingly obvious” from the documents that banks had not followed their own rules while lending to Mallya’s companies.

A highlight of the hearings in the Westminster magistrate court has been the ways in which the Indian news media figured inside and outside the court. Mallya used the opportunity provided by live television to present his version of the narrative.

At every hearing, a media scrum would gather outside the court when Mallya arrived, again during lunch break when he would step out for a break, and then again as he left the court premises. On some occasions, he appeared pensive and tense but mostly seemed to enjoy the attention.

Inside the court also, the Indian news media came under sharp focus. News reports were often mentioned to make points while concerns were raised over “media trials” allegedly influencing the judiciary in India.

Martin Lau, a law expert and Mallya’s witness, said: “There is an increasing concern in India about media trials. There has been a proliferation of television channels, panel discussions with powerful TV commentators. They are liable to influence all aspects of the trial. There is intense media interest in India in this case.”

Academic Lawrence Saez, also Mallya’s witness, admitted that a substantial part of his criticism of the CBI was based on press reports. “India has an established democracy and a free press. Many newspapers are prestigious. They follow the British model of fairness; some are replicas of The Times of London. They can be trusted, unlike the press in countries such as China,” he said.

“There is a competitive news market. Inaccuracies would be pointed out by rival newspapers. Communication between the government is accessed by journalists in India as in other countries, through informal networks of individuals or leaks,” he said.

In one of the first hearings, Mallya’s lawyer asked the judge for a direction that media personnel be barricaded outside the court to prevent him being accosted every time he entered or left the court. However, she said she was not sure if she had the power to do so.

The Mallya case is also significant in the context of the 1993 extradition treaty. Only one individual has been extradited so far. Samirbhai Vinubhai Patel, wanted in a case related to the 2002 Gujarat riots, was extradited in October 2016.

The Mallya case has been argued by two highly respected lawyers with Queen’s Counsel status: Summers for India and Claire Montgomery for the defence. The defence team also includes Anand Doobay. The three — Summers, Montgomery and Doobay — have co-authored a book on extradition law.